Given the state of the world lately, it seems like as good time as any to take a look back at the TV movie, The Day After, a unique piece of television “entertainment” that aired on November 20, 1983.

I put the word “entertainment” in quotes since the movie was about a nuclear war, and while it was gripping and harrowing and interesting, entertaining isn’t the first adjective that comes to mind when describing this film.

Still, if you want to look back and remember what all the fuss was about, let’s do just that…

Today's "TV Lesson" Breakdown:

The Plot of “The Day After”

Honestly, as somebody who saw The Day After when it aired, and granted, I was only 13 years old, what I remember is the months, weeks and days leading up to the airing of the TV movie far more than the actual movie itself. Which isn’t to say that the movie wasn’t memorable – it was – but what has likely stayed in the memory banks of most Americans during that time is the second half of the movie far more than the first.

The first part of the movie follows various families in Lawrence, Kansas, and Kansas City, Missouri, the two cities in the film that were targeted by – you guessed it – the Russians. That said, it’s never clear in the movie – purposefully – who was the first to send off nuclear missiles. The point of the film wasn’t to make the Russians look bad. The point of the movie was to drive home the idea that it would be a very bad idea for any country to ever have a nuclear war. Full stop.

Anyway, the first half of the movie, you’re watching it, full of dread, and not caring all that much about the characters because what they’re going through seems so low-stakes, and it is.

But the tension keeps building. As a kid, I was bored, but as an adult, re-watching it, I was riveted. When there's action between the Soviet Union and the United States -- they're firing missiles at each other but not nuclear bombs, there's a scene of panic among shoppers in a supermarket, as everybody rushes to stock up on supplies in case of a nuclear attack. This was filmed in 1983, but you can't help but think about the days of toilet paper and paper towel hoarding during the spring of 2020 when Covid-19 seemed to be lurking at every corner, and people were panicking.

The second half of the movie morphs into a nightmare movie, a horror film, to be sure, but not one that you can enjoy. Nuclear bombs fall, and a lot people evaporate. You see their skeletons in a flash of light, and then they are gone. Honestly, it’s a little like watching what I imagine it would be like, if a big chunk of the sun fell onto the Earth. It is harrowing, even watching it today. The special effects are pre-CGI, but they look real enough. There are dust-fire storms. Children and parents powerless to save them die in an instant. It is literally Hell on Earth.

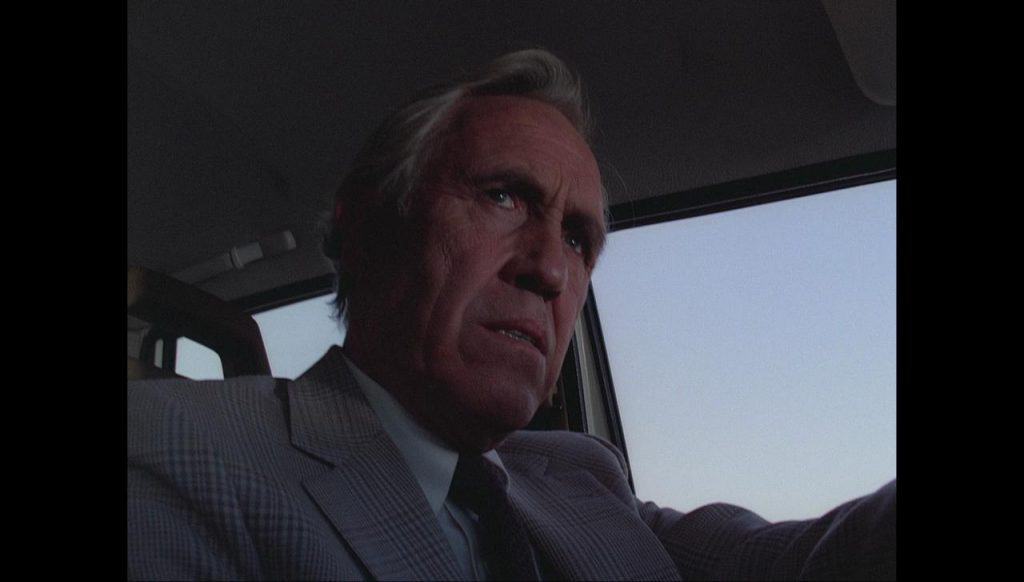

You will be relieved to know that if you happen to own a 1981 Volvo GL, and there is a nuclear disaster, you may end up surviving if you’re lucky enough to be in one when the blast occurs. Dr. Russell Oakes, played by Jason Robards, is driving one when one of two nuclear bombs land in the distance. His car has stopped – as have all the vehicles on the freeway, including motorcycles – thanks to what is known as an electromagnetic pulse. And when that first bomb drops, Dr. Oakes ducks, hugging the seat, and apparently because of that, he survives – not one but ultimately two nuclear bombs that have landed on the horizon. Yes, there is a second nuclear bomb off in the distance. The 1981 Volvo GL is one heck of a car.

But other than that, there is nothing amusing or entertaining about these scenes or the movie. Before the blasts, people run, terrified. After the blasts, some people run, but not for long before the blast and nuclear fire overtakes them. An entire wedding party is disintegrated. It’s gruesome.

After the nuclear blast, the movie focuses on, of course, the day after. It is grim.

Dr. Oakes leaves his car and walks through a desolate landscape until he reaches the hospital he works at.

When he does, the hospital has no electricity, and it’s overrun by citizens needing medical help. But it’s kind of inspiring to see the hospital staff doing their best and trying to go on with their jobs and assist everyone, just as we've seen in countless real life tragedies. Dr. Oakes is stunned but quickly starts to find his footing and takes a leadership role in calming the crowd of patients and helping the hospital to get back to normal. Well, something resembling normalcy.

It’s soon clear that nothing – at least in this part of the country – is going to be the same. Later, it becomes more clear that this was a nuclear attack that probably went far beyond Kansas and Missouri.

In the basement of the Dahlbergs, a family who rode out the nuclear blast in their basement, a mom (Bibi Besch) tells her husband Jim (John Cullum), “We’re lucky to be alive.”

“We’ll see how lucky that is,” Jim says.

Jim is unfortunately right. Later, when the older daughter freaks out and runs out of the house, a pre-med student named Stephen Klein (Steve Guttenberg) taking shelter with the Dahlbergs, runs after her and convinces her to come back to the house, because while the sky is bright, there are dead farm animals everywhere.

It’s not safe to be out here, Klein asserts, telling the young woman about the radiation poisoning. "You can't see it. you can't feel it. But it's here, all around us. It's going through us like an X-ray, right into our cells,” Klein says.

Klein is correct in his diagnosis. If he had lived long enough, he clearly would have made an excellent doctor.

Poor Jim Dahlberg is shot to death by a squatter on his own land.

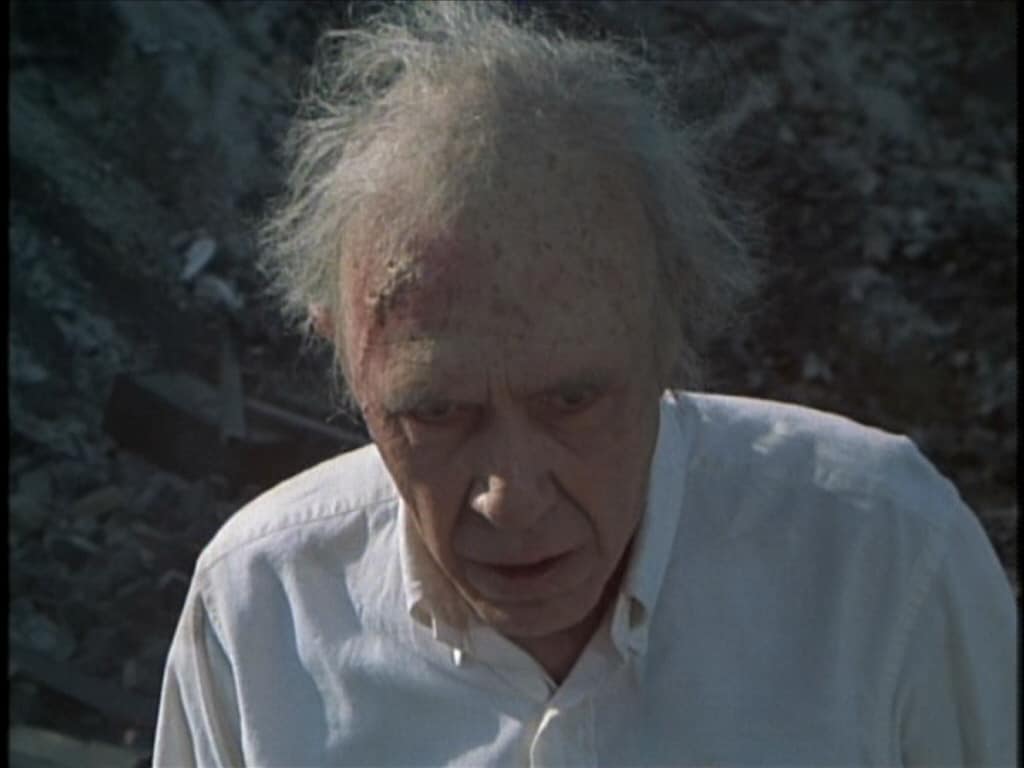

The radiation poisoning eventually catches up with Dr. Oakes. Apparently his Volvo didn’t really provide all that much protection after all, and the movie doesn’t exactly end on a happy note. Dr. Oakes leaves his hospital, recognizing that he is slowly but surely dying. He would like to see his house before that happens, though. He hitches a ride with an army truck and gets to see two men, on the side of the road, about to be executed by a firing squad. Reasons, unknown. This is a new world, we are in.

The movie ends with Dr. Oakes, at his home, slowly perishing of radiation poisoning and being hugged by another man, also dying from the nuclear fallout. The last thing viewers hear is a scientist, played by John Lithgow, trying to contact other survivors of the holocaust with a shortwave radio.

“Hello? Is anybody there? Anybody at all?”

He is met with silence.

After that, the screen reads, in part:

"The catastrophic events you have just witnessed are, in all likelihood, less severe than the destruction that would actually occur in the event of a full nuclear strike against the United States."

A feel-good movie this was not.

Stray Observations about “The Day After”

- The brainstorm for The Day After came from an ABC executive, Brandon Stoddard, who got the idea after seeing the 1979 movie, The China Syndrome, starring Jane Fonda, Michael Douglas and Jack Lemmon, about a nuclear power plant meltdown.

- Edward Hume, creator of several TV series, including The Streets of San Francisco and Barnaby Jones, was tasked with writing the screenplay.

- The Day After had interesting timing when it ran. Six days earlier, the first American-made cruise missiles planned for deployment in Western Europe arrived in Britain.

- From Tom Shales review in The Washington Post: "There are no gory effects, only horrifying ones, and no attempts to duplicate the grisly scenes of Hiroshima survivors that have been shown as part of TV newscasts and documentaries. In the second hour of the film, people suffer and die. The area around Lawrence, Kan., where most of the action takes place (and where the movie was made on location) becomes a society of stragglers, wanderers, looters, poachers--and corpses, some of them buried in mass graves. A man who survived nuclear attack is shot dead by homeless nomads who are victims of radiation poisoning. The picture of a post-apocalyptic world is unrelentingly bleak, as depressing as anything ever depicted in a television drama."

- Jason Robards was as good a person as any to play the doctor in the midst of a nuclear war. He had certainly experienced his share of tragedy in his life. An alcoholic, he gave up drinking shortly after a 1972 car wreck, in which his Mercedes went over a guard rail on a treacherous road in the California mountains. He was reportedly taken to the hospital with no heartbeat and then revived. His entire face had to be surgically reconstructed.

- The movie had a solid cast, including the respected dramatic actors Jason Robards and JoBeth Williams, fresh off of the movie Poltergeist and playing a nurse in The Day After, and up-and-comers like John Lithgow. Steve Guttenberg was another year away from Police Academy coming out and making him a household name. But there were many people whose names were not famous, or like Guttenberg, not yet famous. That was done on purpose. Nicholas Meyer said in an interview with TV Guide, "What we don't want is another Hollywood disaster movie with viewers waiting to see Shelley Winters succumb to radiation poisoning."

The Day Before, “The Day After”

What I personally remember about this TV movie is that it was a cultural event. I recall the build up to the movie more than the story itself. Back in the 1980s, sometimes TV movies and miniseries were pretty big deals, and audiences would really get excited about watching them, but for every Shogun (a TV miniseries from 1980), there were dozens of movies that aired and were barely noticed by critics or audiences.

The Day After was not one of those. The TV movie was written about extensively in the newspapers, and numerous stories on entertainment programs covered it. It was very controversial at the time. You had anti-nuclear activists and pro-nuclear camps seeing the movie in different ways and wondering how the country would be affected by the film. Would the movie glorify nuclear war? Would the movie scare the country into getting rid of its nuclear arsenal and leave the United States defenseless?

Over a month before the TV movie aired, Tom Shales in The Washington Post wrote of The Day After, “It could well become the most politicized entertainment program ever seen on network television, a fact that has jitters spreading like a virus through ABC executive suites."

Shales also wrote, in another Washington Post article, one that ran two days before its TV debut, on Nov. 18, 1983, "As has rarely happened in television history, a work of fiction has achieved the urgency and magnitude of live coverage of a national crisis. One can imagine an ABC engineer quivering slightly as he presses the button on Sunday night that will send the film into millions and millions of American homes. Despite some predictions to the contrary, those homes and the psyches in them are certain to survive it. Nor will the republic likely perish from exposure to this highly convincing nightmare."

The movie was going to run two nights as a four-hour miniseries, but ABC lost its nerve on that and shorted the film into one that was 2 hours and 15 minutes, including a smattering of commercials. For good reason. The Day After was rattling the country. The fear of the movie was more palpable, perhaps, than actually watching the film, which inspired anti-nuclear demonstrations and candlelight vigils. Keep in mind, this was a TV movie that was airing. Not a real event.

Nonetheless, schools across the country sent letters to parents, suggesting that kids under 12 not watch the movie.

A memo sent out to the New York City school system explained the school board’s thinking: "ABC's intention in presenting it is to educate the public about nuclear war. However, the scenes of terrible destruction, people being vaporized, mass graves, and death from radiation sickness may not be helpful or educational for children and young people. This is not just one more horror film. Adults can confidently tell youngsters that ghosts and vampires don't exist. But the threat of nuclear war is real."

ABC, however, apparently did hope students – at least older ones – would watch the film. The network distributed about half a million viewer guides across the country, sending them mostly to schools.

The Physicians for Social Responsibility, which had 20,000 members, advised doctors to be prepared to counsel traumatized viewers.

Advertisers were suddenly leery. Would viewers see images of a person’s face melting off, and then there’s be a commercial break with somebody snacking on Pringles?

ABC decided to make part of The Day After an ad-free experience. No TV commercials would run once the fictional nuclear weapons were fired.

An estimated 100 million people sat down to watch The Day After, my parents, younger brother and I, among them. I was 13 years old. My brother, 11.

You’ve gotta feel sorry for the 1983 TV miniseries, Kennedy, that went up against it on NBC, which may have well been an excellent piece of entertainment. It certainly had a solid cast going for it. Martin Sheen starred as President John F. Kennedy, getting in some good practice for later playing President Bartlet on The West Wing. John Shea, who was later the villain Lex Luthor in Lois & Clark: The New Adventures of Superman, co-starred as Robert F. Kennedy. Kelsey Grammer of Frasier fame was Stephen Smith, John F. Kennedy’s brother-in-law. Nobody remembers Kennedy today.

The Day After, “The Day After”

I can’t speak for others, but once it was over, I remember my parents and brother and I looking at each other, with kind of depressed and stunned expressions, and then we all went to bed. My parents had to go to work the next morning, and my brother and I had school. But to this day, I still remember seeing Jason Robards’ haunted, gaunt face, near the end of the movie. His hair is falling out. His skin could use some moisturizer.

The country moved on, of course, but The Day After may have done what it set out to do – it did remind humanity that nuclear was is not something to be trifled with. The message of the movie was more than clear: many people will die in a nuclear war, and the ones who live may well wish they had died.

President Ronald Reagan saw The Day After before most people in the country. He watched it on October 10, over a month before it aired, and he wrote in his diary that night (I assume that night):

“Columbus day. In the morning at Camp D. I ran the tape of the movie ABC is running on the air Nov. 20. It’s called “The Day After.” It has Lawrence Kansas wiped out in a nuclear war with Russia. It is powerfully done—all $7 mil. worth. It’s very effective & left me greatly depressed. So far they haven’t sold any of the 25 spot ads scheduled & I can see why. Whether it will be of help to the “anti nukes” or not, I cant say. My own reaction was one of our having to do all we can to have a deterrent & to see there is never a nuclear war. Back to W.H.

The Day After was nominated for 12 Emmys and won two of them, for sound editing and visual effects, but as The Hollywood Reporter has pointed out, it’s real legacy may have been in how Reagan was affected by the movie. In 1987, after co-signing a nuclear treaty with Mikhail Gorbachev, Reagan sent a telegram to Nicholas Meyer, the director of The Day After.

“Don’t think your movie didn’t have any part of this,” Reagan wrote. “Because it did.”

That's kind of mind blowing, if you think about it. That we haven't had a real life sequel to The Day After may be due to the efforts of people like a TV network executive, a screenwriter, a director and, well, an entire army of Hollywood professionals. The next time any of us happen to see Steve Guttenberg or JoBeth Williams around, we should give them our thanks.

Where to watch The Day After (at the time of this writing): The 1983 TV movie unfortunately, and kind of inexplicably, can’t be found anywhere for free (please correct me if I am wrong), except on YouTube.com.

Articles similar to this The Day After story: This is the only article on the website about nuclear war, but you may be interested in another – much lighter – TV phenom, known as the Dallas episode where everyone finds out the answer to the question, “Who shot J.R.?”

Beau Gilson

Remember this movie. Was in 11th grade and was mandatory that we watch it for a class. Think it changed everybody's mind about nuclear weapons.