If you’ve ever been tricked out of hard-earned money, you are hardly alone. In fact, if you want a a crash course in how not to be scammed and a reminder that the art of the con is an age-old tradition, you’d do well to sit down for a spell with police sergeant Joe Friday and binge watch that timeless TV classic – Dragnet.

For those of you familiar with Dragnet, you may be rolling your eyes – or nodding in agreement. It could be an incredibly cheesy TV series, but weirdly compelling, too, with its two stalwart cops on the beat -- Joe Friday and his series of partners throughout the series, which started off on radio before gravitating to television.

Those partners were, in case you were wondering, Sgt. Ben Romero, Sgt. Ed Jacobs, Officer Bill Lockwood, Officer Frank Smith and Officer Bill Gannon.

Every episode would have an announcer intoning, "The story you are about to see is true. The names have been changed to protect the innocent."

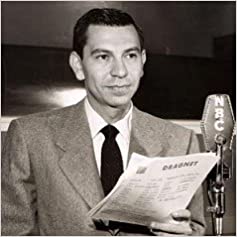

Then we would hear narration from Sgt. Joe Friday, played by Jack Webb, that began with: "This is the city: Los Angeles, California. I work here. I'm a cop." And Friday would proceed to tell us something about Los Angeles before explaining the events of this week's episode.

During the Dragnet TV series, which ran from 1951 to 1957, and then, again, this time in color episodes, from 1967 to 1970, Friday and his partners came across just about everything you can imagine a police officer coming across—murder, drugs, burglaries, dognapping, domestic abuse—and, yes, scams.

So what can we learn about grifters and being taken from Dragnet? Well, let’s take a look at some of the cons that crooks attempted to get away with – unaware that Joe Friday was on the case.

Today's "TV Lesson" Breakdown:

A Dragnet episode from 1953: The Big Betty

The scam: Armed with information from the newspaper's obituary section, con men scam family members who have lost a loved one.

For instance, in "The Big Betty," Friday and his partner Frank Smith (Ben Alexander) talk to a woman who looks to be maybe 20 or 21 and was engaged to a soldier, killed overseas.

As the woman, Miss Bergstrum, tells Friday and Smith, a man named Spencer came to her front door, with a watch and a pen and pencil set.

“He said Harry had ordered these things as presents for me,” Miss Bergstrum tells Friday and Smith.

According to Spencer's story, Harry had asked him to deliver the gifts to her house. Apparently, good ol’ Spencer had bought the gifts and expected Harry to reimburse him. Hoping to do the right thing and wanting these gifts that her fiancé wanted her to have, Miss Bergstrum paid Spencer $48 for the watch and $30 for the pen and pencil set.

Later, she learned the watch didn’t work, nor did the pen and pencil set, and she wound up contacting the police.

"I guess I should have been more careful, but I didn't think anybody would do a thing like that,” Miss Bergstrum says.

Similar scams before the Dragnet episode: I have a feeling the “obituary racket,” as cops would refer to it, goes back pretty far. For instance, going through newspaper archives, I found a New York Times article from 1931 that reported on two young men who combed the obituary columns – and then would send through the mail C.O.D. packages addressed to the deceased.

C.O.D. means “collect on delivery,” and it’s a service that the post office still has – where the sender agrees to pay for the mailing charges.

The two men would pay 35 cents to mail these packages, but the C.O.D. charges were listed for $4 to $5, a pretty good sum in 1931 – in fact, $5 in 1931 would be about $90 today. Inside the packages were secondhand items, like cigarette and handkerchief boxes, from the guys’ homeland of Russia. Today, those items would probably be worth a lot; back then, not so much.

Another interesting article I unearthed: in 1936, the Associated Press reported that Joseph C. Lauzon, 47, an ex-con, was arrested in Atlanta. Lauzon had just gotten out of prison the year before for larceny, and what did he do once he got out?

He started reading obituaries in New York, Philadelphia and Washington newspapers -- and began writing letters.

The recipients of the mail would learn that their dearly departed had lent Lauzon money, sometimes $50 and sometimes $100.

Lauzon would ask for that money back, saying he was "down and out and needed the money."

Some relatives paid the debts; others smelled a rat and got the police involved.

Similar scams today: According to an article from last year in AARP, and you can find similar tales in local news media, crooks are still reading obituaries (only now they read online obituaries) and seek out family members to con out of money. If it’s a scam that works, crooks don’t care how old it is.

Worth mentioning about “The Big Betty.” I won’t say what “The Big Betty” refers to in case anyone wants to watch this episode, but it’s always fun to see Joe Friday dress down a crook. In this case, the criminal is a sharp-dressed and smooth talker named Wesley Fisher, who was such a good con artist, at first, when watching the episode, I kept thinking, "Friday and Smith have got the wrong guy. He didn't do it."

No, Fisher did, which is why Friday lectures him big-time:

“No, you listen, you two bit thief. I couldn't begin to tell you off for the rotten things you've been pulling off in this town for the past three months. That young girl who lost her boyfriend overseas, that widow out in Hollywood, the old man in Highland Park whose wife passed away. You must have felt real sharp cheating them out of a few bucks. Maybe you don't remember, but we do and they do, and you're gonna pay for it, mister. You're gonna pay good."

Sgt. Joe Friday

The dialogue in Dragnet may have not always been realistic, but you have to admit, it had a certain film noir panache to it.

As Fisher later tells Joe Friday and Frank Smith when he decides to confess and rat out the rest of his gang: “They're in it just as deep as I am. If they can't do right by me, I'll square it up myself. I'll tell you everything I know.”

An episode from 1953: The Big Lover

The scam: We’ll keep this rundown short. Joe Friday and Frank Smith investigate a con man who marries women for their money. The crook runs ads in the personals section of the newspaper, and then soon after meeting them, he proposes to them, and once they’re married, he leaves – with their money.

Similar scams before the Dragnet episode: This is another scam that is so common in real life, that there are probably hundreds or thousands of examples of this happening over the years, sad to say. But I’ll share a story I found in the Detroit Free Press and several Indiana newspapers.

The year was 1901. On June 28, a man came to the front door of a Matilda Runkle's house in Edwardsburg, Michigan, and introduced himself as old school chum George St. Clair, who had wanted to marry her since they were kids.

There apparently was a George St. Clair in the widow Runkle's life, and according to papers, she told the man that he looked nothing like her beau. But St. Clair insisted that he had gained weight over the years and just looked different. In any case, Matilda – or Tillie, as everybody around town called her -- decided that this earnest man must be telling the truth.

Tillie was either 56 or 58, depending on the newspaper you believe, and twice widowed. She apparently really wanted to believe that this was St. Clair, because she not only accepted his story, she also soon accepted his marriage proposal.

The day after accepting the proposal, with Tilllie’s blessing, St. Clair went into town for a marriage license. It took him awhile to get it, but he returned in the evening, late enough that he had to wake up Tillie Runkle, who had gone to bed. They got married, presumably in the living room and with some neighbors as witnesses.

Soon after, George had to go into town again -- to buy shingles for their roof, according to several newspaper accounts – and he asked Tillie for $11. She forked over what in today’s dollars would be over $300, and he left. He did not return.

Later, it came out that George St. Clair was actually William Frazier, a safe cracker, bank robber, door-to-door salesman of worthless salve and an ex-convict who had several aliases, including George Wilson and George Skinner and at least half a dozen other names. Matilda Runkle, who died several months after his proposal, apparently of natural causes, was not his first victim either. Frazier was arrested later in the year and pled guilty. What exactly happened to him, I can’t say, but presumably he was escorted back to the slammer.

Similar scams today: These days, con artists are much more likely to con lonely people out of money through online dating sites by developing a rapport and relationship without meeting in person – and, of course, finding reasons to ask their newfound boyfriend or girlfriend to send them money.

According to the FBI, just this year alone – and the year isn’t over yet – people have lost $133 million to dating scams.

Worth mentioning about “The Big Lover”: As with many of the early Dragnet TV episodes, this one was based on the March 29, 1951 radio play. Dragnet was on the radio from 1949 to 1957, so you could listen to the series on the radio and watch it on TV. (On TV, as earlier noted, Dragnet aired from 1951 to 1957, and then returned to the tube from 1967 to 1970.)

A Dragnet episode from 1967: The Subscription Racket

The scam: Sgt. Joe Friday and Officer Bill Gannon catches a scam artist who has an interesting prop – an actual Congressional Medal of Honor that he is using to solicit magazine subscriptions.

Similar scams before the Dragnet episode: The crook having in his possession an actual Congressional Medal of Honor is pretty rare -- you don't see that every day -- but fake magazine subscriptions is a time-honored con, as common as a sunrise. I found a Altoona, Pennsylvania newspaper article as far back as 1912 that referred to a guy in Toledo who was going around a neighborhood, selling fake magazine subscriptions.

Quincy, Illinois’ paper in 1915 reported on a guy who was caught selling fake magazines – and sentenced to 30 days in a “workhouse.”

There are newspaper articles from the 1920s, 1930s, 1940s, all mentioning fake magazine subscription scams – it’s such an easy con, unfortunately. You look presentable and have materials that make it look like you work with a magazine. You sell the subscription and take the money upfront. You do your best to never see your "client" again.

Similar scams today: You can find a lot of cases in today's media where crooks are being arrested for selling fake magazine subscriptions, and it's really sad. Especially for the victims, but it’s also not so hot for the magazine industry. As a writer who used to write for a lot of magazines before the internet took over, I really hate to see crimes like this. Magazines had a rough time adjusting to the internet; they don’t need criminals besmirching their reputation.

Earlier this year, the FBI charged 60 people involved in a telemarketing fraud scheme that they called “the magazine case,” which took aim at the elderly. It was a 20-year-long scam in which 150,000 people from 50 states were tricked into paying for fake magazine subscriptions. Some people lost hundreds and thousands of dollars; some people were tricked out of over $50,000.

Worth mentioning about “The Subscription Racket”: Early in the episode, Friday appears on the fictional local program, The Jerry Dexter Show, to be interviewed about how to not be scammed.

Friday then proceeds to tell Dexter and the TV audience all about the scams that were being foisted on victims during the 1960s. We learn about three common cons:

The rubber rattlesnake con. A con artist comes to a home in an area known for rattlesnakes. The scammer offers a free search for rattlesnakes. The homeowner gratefully agrees. The con artist searches the premises and returns with a rubbery rattlesnake that looks real – and says that there’s a whole nest of them. The con artist says that he’ll be glad to get rid of the rattlers – for a fee, of course.

The tree branch scam. Friday says that a con artist convinces a homeowner to let them trim trees and charges a small amount of money per branch that they remove. Sounds reasonable, the homeowner thinks, and hires the person. Then the con artist – and often his team – go to work. They bring back a lot of branches, far more than the homeowner expects, many of them twigs. They want to be paid for everything, no matter how small the branch, which adds up to, well, a lot. The homeowner eventually pays something, just to end the argument and get the “tree trimmers” off the premises.

The money making machine scam. Friday demonstrates a machine that can supposedly make money. If used properly, it does look like a con artist is making money – it’s basically a magic trick, involving a false bottom and cash hidden that the crook later shows as proof that paper has been turned into money.

It looks like the dumbest thing ever, and like something no sane person would ever have fallen for, I don’t care how naïve people were in the 1960s. In fact, I thought, “This has to be something that happened once, and Dragnet is running with it.” But, no. A newspaper archive searched turned up numerous articles about this scam, which seems to have started in the 1910’s and gone into at least the early 1970’s.

An episode from 1968:“The Badge Racket”

The scam: Businessmen go to a hotel and find themselves invited into a hotel room to gamble – and then a beautiful woman ends up joining them. Soon after, “vice cops” raid the hotel room, and here’s where the scam in this episode gets really interesting.

As a fellow cop tells Joe Friday and his partner, Bill Gannon (Harry Morgan), the fake vice cops actually take their businessmen victims to an actual Los Angeles police station, the very one Friday and Gannon work at.

“It’s a public building,” Gannon points out, adding, “but it sure sounds like the hard way, doesn’t it?”

The way it worked, Friday and Gannon are told, one vice cop went onto a floor somewhere, pretending to do paperwork, and the other vice cop took the victim to the cafeteria. Later, the second cop joins them and discusses bail.

The victim, at the police headquarters, and seeing fake badges and fake police paperwork, naturally figures that he really is in danger of being arrested. But in this recent case on Dragnet, a businessman, later realizing he had been swindled, reported the matter to the police.

So before too long, Gannon ends up posing as a businessman, hoping the con men will do the con on him, and of course, that’s just what happens.

Similar scams before the Dragnet episode: Many a bad guy has pretended to be the police. There are too many examples throughout history to name – but one stands out for me. In 1954, the Associated Press ran a little story about a check forger in San Antonio who was passing bad checks with the name G.O. Covington. Every time the crook would give his checks to a store owner, he made sure that they saw his police badge, which was fake.

The name was real, though. In fact, G.O. Covington was a long-time police officer. Covington was probably pretty embarrassed by the bad checks being passed around the city. Because at the time, his beat was catching people who passed bad checks.

Similar scams today: It happens around the country more than one might think. Local media is full of stories of bad guys not just wielding fake police badges but driving cars hooked up with strobe lights and pulling people over – and of bad guys arresting homeowners and then robbing them. Be careful out there.

Worth mentioning about “The Badge Racket”: Harry Morgan’s character Bill Gannon has some nice moments in this episode, always able to offer up a little dose of humor in a TV series that was mostly humorless, at Jack Webb’s direction.

Of course, given the success of Dragnet, and it’s status as a TV classic, it’s hard to argue that Webb didn’t know what he was doing.

At the beginning of this episode, Gannon is putting in what looks to be eight sugar cubes in his coffee.

He talks about how adults (“grown kids”) like sugary cereal and athletes eat candy bars and offers up this gem: “What do you give a race horse to make them run faster? Sugar cubes. Yes, sir, salt of the earth, sugar.”

Actually, Gannon had some interesting ideas in general about food, as we learn throughout numerous Dragnet episodes. For instance, the secret to making Gannon's barbecue sauce? A quart of ice cream.

Some More Financial Advice from Joe Friday

Watch Dragnet enough, and you won’t only pick up information on scams to be aware of, you’ll get some decent all-purpose, general financial advice as well. Some money tips, courtesy of Sgt. Joe Friday…

Spend wisely; try to have funds for retirement. At the beginning of the episode, “The Bank Examiner Swindle,” Friday does his usual narration, to go along with various shots of Los Angeles, and he offers up the advice, "You can live pretty good in Los Angeles on a pension, if you're careful.” (I'm not saying that all of his advice is surprising or groundbreaking.)

Don’t keep your life savings in your home. After all, what if you were robbed? Or if there was a fire?

In a 1969 episode of Dragnet called, “Bunco: $9,000," Friday gives a woman some friendly advice.

“Mrs. Perriwinkle, you really should put your money in a savings account. You know that. You're taking a dangerous risk hiding it here,” Friday says.

“A bank? Never. Don't trust them, never will. Never! Anyway, money is not my god. The Lord is my god.”

“Yes ma'am, but a bank is still a good place to keep your money,” Friday says.

Time really is money. And it would probably behoove us all to have a better idea of how much our time is worth.

In the 1954 Dragnet movie – which came out while the TV series was on the air – we see that Friday really understands what each minute of time costs him. a mobster named Max Troy asks how long an interrogation is going to take.

“You’ve got the time,” Friday says.

“Mine’s worth money. Yours isn’t,” Troy says.

After some back and forth, Troy asks Friday how much money he makes.

“What do they pay you to carry that badge around? Forty cents an hour?” sneers Troy.

“You sit down,” Friday says. “That badge pays $464 a month. That's what the job's worth. I knew that when I hired on -- $67.40 comes out with withholding. I give $27.84 for pension, and 12 bucks for widows and orphans. That leaves me with $356.76. That badge is worth $1.82 an hour, so, Mister, better settle back into that chair because I'm about to blow about 20 bucks of it right now.”

If it sounds too good to be true, it probably is. In “The Subscription Racket,” Sergeant Joe Friday explains to talk show host Jerry Dexter how people wind up falling for certain outlandish scams, like the money-making machine one: “Well, it's people's own greed that makes them victims of the bunko artist, trying to get something for nothing.”

How to not be scammed? Go with what you know. It's best to not use the services of a company that shows up at your house – unless you actually know the brand – and to be wary about paying a complete stranger for any services or products.

As Friday tells Dexter’s TV audience, “Well, you're always safe with reputable established firm with whom you've dealt before or who are recommended by friends.”

Good advice then, and good advice now.

Where to watch Dragnet (at the time of this writing): You can find Dragnet on the cable channel MeTV as well as some of show (I'm not sure if it's anywhere in its entirety) on streaming services like PlutoTV.com.

Articles similar to this one: This is the only Dragnet heavy one so far, though Joe Friday and Bill Gannon appear in a couple other stories. That said, you might enjoy picking up car purchasing tips (and how not to get scammed buying one) in this post, which details some of the headaches Greg Brady, Barney Fife and others went through when buying a set of wheels.

Leave a Reply