The classic TV western Bat Masterson wasn't exactly a documentary. A film crew didn't follow around the legendary lawman and professional gambler Bat Masterson, filming his exploits across the Old West. (Ah, if only that were true.) Still, while the TV series, which lasted from 1958 to 1961, took a lot of liberties with the truth, it occasionally did brush up against some actual history. As it did in the episode, “The Picture of Death," inspired by the photographer, Eadweard Muybridge.

I recently stumbled on the episode while channel streaming – I guess that’s what you would call it – on PlutoTV, a free service with ads. I found myself watching a little of Bat Masterson, a show I heard about growing up but never actually saw until several years ago, probably on the cable channel MeTV. Anyway, I was gamely watching the episode, and then something happened where I realized, “Hey, this was based on a real event.”

And soon I was falling down the research rabbit hole that is both Bat Masterson and the real Bat Masterson.

Today's "TV Lesson" Breakdown:

A Few Words on the TV series Bat Masterson

So, really quickly, for those who aren’t familiar with the series, Bat Masterson starred Gene Barry, a former Broadway actor who, like many performers, started finding work in the early days of television. Barry’s first TV appearance was in 1950 on a suspenseful anthology series called The Clock. From there, he began popping up on TV everywhere. Still, it was Bat Masterson where he really broke through.

The plot of every episode was basically this: Bat Masterson is in some new town or city, and he gets into some trouble or tries to save somebody from trouble, and then the bad guys look like they’ve got him, but, no, they don’t. Bat Masterson saves the day. The end.

Barry was charming, suave and debonair, and the series was well written. It often looks like most TV westerns that were dominating the landscape during the 1950s and 1960s, but there’s a reason people still watch Bat Masterson. It was entertainment. Formulaic, to be sure, but it was good formula.

But “Picture of Death,” in particular, stands out.

What happens in “Picture of Death.”

A lot of these half hour TV westerns managed to be extremely economical in how they presented their stories, and Bat Masterson was no exception. This was an episode in which the entire plot was detailed in about a minute or two. We see Bat Masterson win a horse race – a form called harness racing, in which a horse pulls a rider in a light two-wheel wagon called a high-wheeled sulky.

In this episode, Bat Masterson is in Tucson, Arizona, in 1882. A local photographer, Mr. Casey (Perry Cook) takes a photo of the winner with a girlfriend of his, Billie Tuesday (Patricia Donahue). It is not a serious relationship, however, given that Billie has her eyes on a guy named Roger Purcell, who we meet almost seconds later.

Moments later, two friends of Bat’s greet him, and we learn almost immediately that they’ve made a bet.

The bet, Hugh Blaine, says, is: “Does a trotter lift all four feet off the ground at the same time?

“That's one of the oldest arguments in horse racing,” Bat Masterson says. “For what's it's worth, I'd say when its racing, a trotting horse has all four feet off the ground.

“It's not worth much without proof, Mr. Masterson,” says Roger Purcell, who has a mustache but doesn’t twirl it.

“You made a bet where the burden of proof is on you?” an incredulous Bat asks Hugh.

“Yeah,” Hugh admits.

“How much is the bet?” Bat asks.

“Exactly fifty thousand dollars,” says Roger Purcell.

“Is this a joke?” Bat Masterson asks.

“If it is, the laugh’s on your friend, Blaine,” Roger Purcell says, telling Blaine: “You’ve got just three days to find that proof… or the money.”

Yes, Billie apparently likes the so-called bad boys. And that, of course, always leads to trouble. Generally in real life and on TV.

Later, when Masterson and Blaine are talking, we learn that Roger somehow got Blaine angry. Furious, Blaine made this bet. Masterson points out that it’s an old trick of a con man, to get somebody to make a bet that they’re sure to lose.

Mr. Blaine asks his old friend for help finding proof that a horse's hooves all lift off the ground when running, but Bat doesn’t see how he could possibly be of service. Then Mr. Blaine tells Bat that he can have 10% of the $50,000 if he can find that proof. Suddenly, Bat Masterson thinks he can find some time in his schedule to help an old friend out.

Masterson talks to a slew of experts, including horse racing judges, but nobody can agree with what they’re seeing. Some think the horse has at least one hoof on the ground at all times; others think the horse does, indeed, have all four hooves off the ground at various moments.

What to do, what to do.

Well, Masterson comes up with an idea. You may have already guessed what he does. He comes up with an experiment, a famous one, in fact, that happened in real life, four years earlier.

1878 and Eadweard Muybridge’s famous experiment

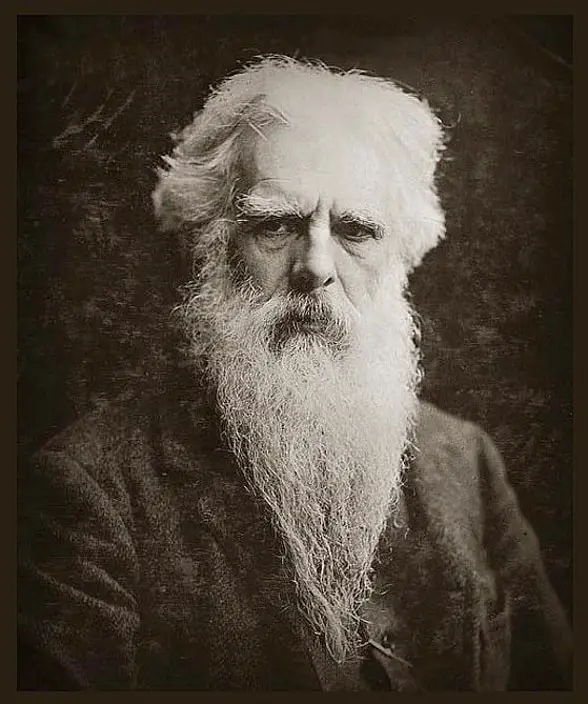

That’s not a typo. Edward James Muggeridge changed his name to Eadweard Muybridge, believing it to be the original Anglo-Saxon form of his name. More importantly, at least for anyone curious about this "A Picture of Death" Bat Masterson episode, he was one of America’s first photographers.

(Eadweard Muybridge is also having something of a reappraisal, of sorts, or at least a cultural moment. He's mentioned prominently in Jordan Peele's recent suspenseful, alien invasion-type, western movie, Nope. I was stunned when, a few months after I first wrote this blog post, I'm sitting in a darkened theater, and I hear the words, "Eadweard Muybridge.")

Muybridge came to America in 1851, from England, when he was 21 years old. The details of his life are a little unclear, but his family apparently had a bookselling business, and he worked for them and another publishing company on the east coast until 1855 when he moved to California and started a bookstore in San Francisco.

In 1860, Muybridge started traveling east, on a stagecoach, with designs on traveling to Europe. Unfortunately, he was seriously injured in a stagecoach accident, thrown from the vehicle, his head landing on a boulder.

Muybridge survived and did make it to Europe, spending that time back in his home of England, recuperating and suing the stagecoach company.

While in recovery mode, a doctor suggested he spend more time outdoors, and Muybridge discovered the art of photography. That would change the course of his life.

Eadweard Muybridge eventually returned to California and became a prominent photographer, especially well known for taking photos of Yosemite Valley and the new territory of Alaska. He took some well-regarded time-lapse photos of the construction of the San Francisco mint.

His work was getting noticed. At least, a businessman and Senator named Leland Stanford noticed. (Stanford, along with his wife, Jane, was also a founder of Stanford University.) According to legend and lore, Stanford made a $25,000 bet that horses’ hooves were all in the air when they ran – but he couldn’t prove it.

Sound familiar?

Historians have concluded that there was likely no such bet – but Samuel A. Peeples, the scriptwriter for the Bat Masterson episode, “A Picture of Death,” wisely went with the legend – and made it slightly more outrageous, with the bet being for $50,000.

At any rate, whether there was a bet or not, what isn’t in dispute is that Leland Stanford hired Muybridge to take photos of horses running and determine if their hooves all left the ground. In 1873, he started taking photos of Stanford’s horse in full gallop with four hooves off the ground, but he wasn’t able to successfully tell if the animal ever was fully airborne for a second or so. For the next six years, Muybridge kept taking photos of horses in motion.

Muybridge, incidentally, was the subject of Edward Ball’s 2013 book, The Inventor and the Tycoon. I haven’t read it yet, but among Muybridge’s many accomplishments, he was also... a murderer. In the midst of his photographic experiments, he learned his wife had a relationship with a drama critic named Harry Larkyns, and Muybridge tracked him down and shot him. There was a trial, but Muybridge was acquitted, even though nobody disputed the fact that it had been premeditated murder. These were different times.

In Muybridge's defense, and he did use this as a defense, everybody said he wasn't quite the same person, ever since he hit his head on that boulder.

Anyhow, Muybridge’s frame-by-frame photos of a galloping horse, which he took in 1878, became world famous and is generally credited with helping to lead to the creation of the motion pictures.

Unless, of course, you believe that Bat Masterson and a photographer in Tucson, Arizona were the ones who actually proved that a horse’s four hooves left the ground when running.

Back to Bat Masterson and “A Picture of Death”

When Masterson comes up with the idea of using a photo to prove that a horse lifts all of his legs off the ground, he goes back to Mr. Casey, who we saw at the start of the episode. They have a talk about whether it would be possible for a photo to provide the proof that a hoarse goes slightly airborne while running. Casey is confident that a photo could prove it, but he says that it’ll be difficult to achieve that.

Masterson suggest that they use 10 cameras, set side by side, with a string attached to each. Once the horse runs by, the animal will trigger the strings and turn on each camera. It’s exactly what Muybridge did, except he used 12 cameras.

Mr. Casey likes Masterson’s idea, but he says it’ll cost a lot. Masterson, hoping to win $5,000, pays Casey $500.

So as you would expect, Casey and Masterson do their experiment with Hugh Blaine there.

“Casey, your name will go down in history,” Masterson says.

Alas, no, it will not. Eadweard Muybridge, on the other hand, will, and all these years later, he isn’t exactly a household name.

Masterson and Casey take the cameras – and the plates inside them, which they will later develop.

From afar, the bad guy and his two henchman watch.

“Masterson's up to one of his old tricks,” says Roger Purcell. “If one of those of those cameras happened to catch the horse with all hooves off the ground…”

“You’ll lose a bet you can’t pay off,” a henchman says.

‘If Masterson keeps the plates,” Purcell says.

The henchman promises that he won’t.

As you would expect, Masterson and Mr. Casey, riding back to town on a wagon, are soon confronted by masked gunman who want the camera plates. Masterson agrees, until, of course, he suddenly disarms the bad guys, who quickly ride away. Masterson muses, "You know, photography can be a dangerous business."

Masterson and Casey go back to the photography studio, and soon, they have their proof. All four horse’s hooves do go into the air while trotting. Masterson decides to tell Hugh Blaine the good news.

"You'd better lock that front door. Our friends might be back,” Masterson cautions.

Of course, what Masterson doesn’t know is that Roger Purcell is nearby, watching the photography studio. He sends a female friend, Billie Tuesday – the woman Masterson was with at the beginning of the episode, although, again, she wants to marry Roger – it’s complicated.

Mr. Casey trusts the woman, and because Billie wants to marry Roger, she agrees to try and get the photos from Mr. Casey.

When Masterson comes back to the photography studio, he finds Mr. Casey, on the floor, alive but in need of medical attention. Mr. Casey explains how Billie made off with the photo, the proof Hugh Blaine needs to win his bet.

Without getting into too much detail, let’s just say that because Roger’s henchmen are hotheads, things don’t work out too well for poor Billie – the title of the episode earns its name, “A Picture of Death” – and that because Billie didn’t think to get the negatives, Masterson is able to furnish the proof Hugh Blaine needs to win the bet. Plus, the town sheriff gets involved and sees enough to know Roger Purcell needs to be put away.

Afterwards, Hugh says, “I don’t know how I'll ever be able to thank you, Bat.”

“The fact is, you can't. I know Purcell can't pay off, so ten percent of zero is zero,” Masterson says.

But Hugh says, “You saved me fifty thousand, and ten percent of that is still five thousand. There it is.”

As Bat pockets the money, he says, “Mr. Blaine, I like the way you think - and pay off.”

Did Towns in the Old West Have Photography Studios?

So right away, I found myself thinking, “C’mon, an old town in the west was not going to have a photography studio. That's nonsense that the scriptwriter came up with.” But after combing through nineteenth century newspaper archives, I now realize that at this point, many cities in the Old West did have photography studios.

I don’t know specifically if Tucson had a photography studio, but in 1884, St. Louis had at least one, and Milwaukee had as many as five photography studios. The Bozeman Weekly Chronicle, in its October 17, 1883, edition, ran a detailed ad mentioning the opening of the Studio of J.J. Bennett, a photography studio on Main Street, in Bozeman, Montana.

A June 5, 1883, issue of the Dallas Daily Herald mentions a "photo-art studio" on 705 Main Street, owned by a W.M. McClellan. He wrote his ad himself and urged people to consider dropping by: "The time has passed for any person to accept a caricatured outline map of their features with a lifeless expression. On the contrary, you should accept only those fine photos, beautiful in light and shadow, easy in position and intelligent in expression; full in detail, a thing of life."

McClellan assured people that all who used his services at his studio “shall be artistically and intelligently represented.”

So Bat Masterson did get it right – by the 1880s, at least some cities in the Old West did have photography studios.

Stray Historical Observations

- So who names their kid, “Bat?” Not Bat Masterson’s parents, Thomas and Catherine. Bat Masterson's full name was actually Bartholemew William Barclay Masterson. “Bat” was a nickname that came out of Bartholemew.

- The real Bat Masterson was a U.S. Army scout, a sheriff and a professional gambler, at various times in the Old West. He was born in 1853 and died in 1921. What is lesser known (unless you’re a Bat Masterson enthusiast or groupie) is that in his later years, from 1903 to 1921, he was a sports columnist in New York City.

- So did Bat Masterson have anything to do with figuring out how to take a photo of a horse – and prove that its four hooves lifted off the ground while running? No, of course not, unless the scriptwriter Samuel A. Peeples knew something nobody did. That said, it’s kind of fun to think that Eadweard Muybridge heard about Bat Masterson and Mr. Casey’s experiment and then took the credit for himself. Eadweard Muybridge had killed somebody, after all. He wasn’t exactly Mr. Ethics.

- Regarding Samuel Anthony Peeples, he was an accomplished writer, having written several western novels. But he also would go onto write a number of Star Trek scripts. There were two TV pilots for Star Trek. The first one failed; Peeples wrote the second one, which was the one that ultimately became Star Trek. Peeples died in 1997, at the age of 79, shortly before his 80th birthday.

- If you’re curious about the gold-handled cane Bat Masterson famously used in the TV show, that was based on a real incident that occurred the night of Jan. 24, 1876, in a saloon in Sweetwater, Texas. Masterson had an argument with a man named Melvin King, who pulled out a gun. In what sounds like a TV episode but actually occurred, a dance hall girl named Mollie Brennan jumped in front of Masterson to save him from King. She was fatally shot, and the bullet went through her and struck Masterson in the groin. Masterson then whipped out his gun and shot and killed King.

Small wonder Hollywood decided to make a TV series about the life of Bat Masterson. They had a lot of actual history to work with.

Where to watch Bat Masterson (at the time of this writing): Bat Masterson can be found on PlutoTV. To the best of my knowledge, there is no Eadweard Muybridge TV series, or Eadweard Muybridge movie, though he is, as noted earlier, mentioned in the feature film, Nope.

Articles similar to this Bat Masterson story: You might enjoy this Cheyenne-themed blog post that offers advice on making friends. Or perhaps you'd like to read about Cimmaron Strip and the history of water towers. And while this post is about how classic TV has handled pandemics, Gunsmoke is one of the shows prominently mentioned.

Leave a Reply