Editor's note: "TV History 101” is a new semi-regular feature on The TV Professor, looking at some of the great moments, and maybe not great moments, worth remembering in TV history. Our second installment? We’re looking not at a TV series but a phenomenon that TV helped create – TV dinners.

The history of TV dinners can be a little like the early days of a TV set with its antennas that looked like rabbit ears: fuzzy.

Today's "TV Lesson" Breakdown:

Although September 10, 1953, is often the date given by history websites as when the first TV dinner was sold, plenty of accounts suggest it was later in the year or early the next. But one thing is clear – by 1954, TV dinners were being collectively enjoyed by millions of Americans, and for better or worse, the family dinner would never be quite the same.

How TV dinners got started

As noted, a lot of the specific details swirling around the history of TV dinners appear to be – so far – lost. It’s quite amazing. It isn’t like this is one of the mysteries of ancient Egypt. It was the 1950s. But memories become fuzzy, and people forget things, and corporations don't always keep meticulous records of every meeting that they have.

So as for the early history of TV dinners, here we go…

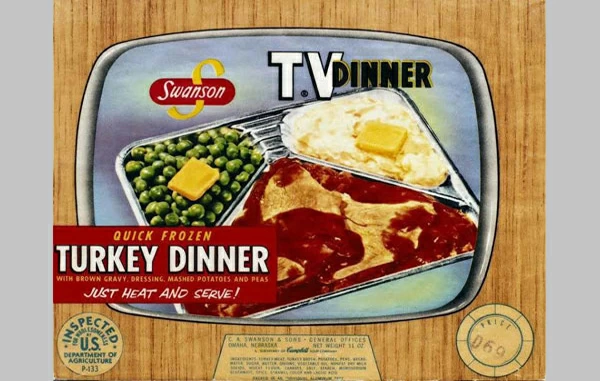

Swanson is the company that is credited for creating the frozen TV dinner in the 1950s when it was then C.A. Swanson & Sons. Its founder, Carl A. Swanson, had passed away four years earlier, and it was then run by two brothers, Gilbert and W. Clarke Swanson. (Campbell’s now owns Swanson.)

Nobody disputes that.

Now, somehow, in 1951 or maybe 1952 and some credible sources even say 1953, the company misjudged the appetite for turkeys on Thanksgiving and wound up with far too many of them, that they couldn’t sell – 520,000 pounds worth of frozen turkeys.

C.A. Swanson & Sons didn’t have the space to store them, and they obviously couldn’t afford to let them thaw out, and so these turkeys were put in 10 refrigerated railroad cars – and while the train chugged along, apparently for weeks or months or maybe years, a clarion call was put out company-wide for people to come up with a solution.

Gerry Thomas was that man. Or not. It seems obvious that he did have something to do with the TV dinners – although just how much is hard to say.

In any case, for some time, Thomas was taking credit for the invention of the TV dinner, and Swanson didn’t dispute his story – but when you’re dealing with any major project at a corporation, generally there are a number of people who can justifiably take credit for something. To paraphrase the old saying, success has many parents, but failure is an orphan.

As the story goes, Gerry Thomas was a salesman for C.A. Swanson & Sons, and he happened to visit the food kitchens of the Pan American Airways in Pittsburgh, where he spotted some single compartment aluminum trays that the cooks used to keep the passengers' food hot.

Thomas reportedly had the brainstorm that Swanson could take those frozen turkeys, cut ‘em up and serve them to people on Earth in a tray similar to what Pan American Airways was doing in the skies above. Thomas also figured that the tray should have some food other than just turkey, and that it should be split into compartments, so the food wouldn’t touch each other.

Thomas had spent five years in the army as an officer during World War II and earned a Bronze Star for his work in breaking a Japanese code. During that time, he had eaten from mess kits, which were essentially packaged trays of food. He didn’t think Swanson should offer up anything quite like that.

“You could never tell what you were eating because it was all mixed together,” he told an Associated Press reporter in 1999.

So as the story goes, Thomas not only came up with the idea to put the food in these three-compartment trays – he also suggested linking the dinners to the nation’s new favorite pastime: watching TV. The packages of food would look like a TV screen, and they would be called “TV dinners.”

What was on TV in 1954

Let’s take a little break from our story to look at the state of TV in 1954 and why Swanson would try offering a meal to be associated with watching television.

In 1954, I Love Lucy was the top-rated program in the country, followed by The Jackie Gleason Show and Dragnet. Milton Berle was still going strong with his variety show. ABC's Disneyland was the sixth most popular series.

Television was a relatively new medium – ten years earlier, TV show hadn’t existed, and the country was in the midst of World War II -- but it was gaining in popularity. We were one year away, incidentally from Marty McFly landing in 1955 in his time-traveling DeLorean and watching a new episode of The Honeymooners, which he had seen before – but now I’m getting off track and with mixing history and fiction and bringing a Back to the Future movie reference into a TV blog, possibly risking rupturing the space-time continuum…

Anyway, my point is – in 1954, TV was a big, big deal, and it’s understandable that some of the executives at Swanson noticed. After all, they were probably watching television, too.

The History of TV Dinners: What was on the Menu

The first TV dinners consisted of turkey, gravy, cornbread stuffing, sweet potatoes and buttered peas. The dinner sold for 98 cents, which in today’s dollars is about $10. So the first TV dinners weren’t exactly cheap – but they were popular. It makes sense, though. If you could afford to buy a TV in 1954, you could probably afford a TV dinner.

After about a year, Swanson was able to lower the price to 69 cents.

We might as well note here that while Swanson was the first company to call their product, “a TV dinner,” frozen dinners and frozen meals in general did already (barely) exist.

In 1925, Clarence Birdseye invented the double-belt freezer, a machine that froze packaged fish. Years later, William L. Maxson helped things along further. Maxson was an inventor (among other things, he created a multiple machine gun mount for the military and a computing gasoline pump), and he was also the founder of Maxson Food Systems, which used Birdseye’s technology to offer meals to military airplanes so that the food could heated and served to its soldier passengers.

After World War II ended, Maxson’s company, needing a new source of income, began offering its products – called Strato-Plates -- to Pan American Airlines.

Maxson planned on selling his meals in supermarkets, but he died in 1947. Newspaper accounts of the time don’t say what he died from, just that it happened after an operation. He was only 49.

So Swanson then was the first to sell TV dinners in supermarkets?

No.

Actually, that honor probably goes to the company Frozen Dinners, Inc., a company run by Albert and Meyer Bernstein, two brothers who in 1949 started selling their products – frozen dinners on aluminum trays with three compartments – under a label called the One-Eyed Eskimo. The Bernsteins' frozen dinners were only selling in Pittsburgh, but they did well.

By 1950, the Bernstein brothers had sold over 400,000 frozen dinners, and two years later, they would form the Quaker State Food Corporation (which has nothing to do with the company, Quaker State Corporation or the Quaker Oats Corporation), and they would start selling their One-Eyed Eskimo frozen dinners pretty much everywhere east of the Mississippi.

So back to Gerry Thomas. Whether or not he should be considered “the father of the TV dinner,” as he was later dubbed by the media, he obviously had a lot of help in its creation. Thomas didn’t make the turkey dinners himself, for instance, and he didn't run the company and thus didn't make the decision to authorize the creation of the TV dinner.

Another hero of this odyssey was Betty Cronin, who the media later dubbed “the mother of the TV dinner.” She started working on the development of the TV dinner in 1953 when she in her early 20s. She was a freshly new college graduate with a degree in bacteriology.

It was her job to find a way to make sure that the turkey, gravy, cornbread stuffing, sweet potatoes and buttered peas would all cook properly at once – so that they were evenly heated.

She told The Associated Press in 1994 that aluminum trays were the perfect type of container for TV dinners.

“Aluminum was the container of choice because it could go from the freezer to the oven. Its weight was light enough to keep shipping costs in line, but the metal trays also were sturdy enough to serve as the 'plate,' " Cronin said.

(Of course, years later, when the microwave became popular, and people began learning the radiation and aluminum do not get along, the trays had to be switched out for plastic.)

The turkey meal wasn’t too hard to get right, Cronin would later say, but the chicken meal – which debuted in 1955 – was much more difficult.

It took Cronin and her team working about 18 months before they had what they felt was a hit.

“Trying to find a breading that would taste good and hold up in freezing was a major obstacle. I began with a simple water and flour breading, but when it was frozen, it separated. There was nothing to pattern ourselves after, so I tried everything under the sun to find breading that would stand up to the freezing,” Cronin told the Associated Press. “It was really trial and error."

The “controversy” over the TV dinner’s origins

In 2003, Cronin told The Los Angeles Times, “Gerry Thomas had nothing to do with the TV dinner.”

Thomas told The Los Angeles Times that Cronin wasn’t in management meetings where he presented his ideas.

In any case, Thomas doesn’t seem to have ever claimed that he did it all. In 1999, he told the Associated Press that it bothered him when the media referred to him as “the father of the TV dinner.”

"I really didn't invent the dinner,” Thomas said. “I innovated the tray on how it could be served, coined the name and developed some unique packaging."

He also is said to have suggested that cornbread be one of the side dishes to the turkey.

Cronin, meanwhile, told The Los Angeles Times that the Swanson brothers, Gilbert and W. Clarke, were the ones who devised the concept – and their marketing and advertising staff, but not the salespeople like Thomas.

Muddying the waters further, trade magazines in the 1950s and 1960s, referred to M. Crawford Pollock, a Swanson executive who worked in sales and marketing, as the guy who deserves credit for the TV dinner.

As noted earlier, my guess is that all of these people played some sort of important role in its success.

As for Thomas’s part, he said that for his efforts, he got a $300 raise and a $1,000 bonus. Thomas would eventually leave the company and go onto do other things, like become a director of an art gallery in New York and started a gourmet pet treat company for dogs. He also served as a councilman in Paradise Valley, Arizona. He was inducted into the Frozen Food Hall of Fame, located in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, in 1998. He passed away in 2005.

Betty Cronin continued to work for Swanson and the parent company Campbell Soup Company (knowing a good thing when they saw it, purchased C.A. Swanson & Sons in 1955). She retired from the company in her 60s and served as a consultant for Campbell and played a lot of golf, according to the Associated Press. She died in 2016.

The legacy of the TV dinner

There’s so much one could say, but it should be obvious to everyone that the TV dinner changed society in many ways, including…

The dinner hour itself. When the TV dinner first debuted, Swanson reported received angry letters from men who were upset that their wives weren’t cooking from scratch like their mothers did for them. (Yes, the poor dears.)

Wives, meanwhile, felt guilty about making such an easy meal, Cronin told the AP in 1994. Kids loved TV dinners, though, according to Cronin. They liked being able to pick out their own meals (once there was more than one TV dinner to choose from), and they loved eating dinner in front of the TV.

That’s certainly part of the unfortunate legacy of the TV dinner – the dismantling of the old-fashioned family dinner where parents and kids sit around a table and eat and talk.

But arguably the TV dinner didn't do all that much damage to the family dinner. At least when families in the 1950s and of the rest of the 20th century were watching TV while eating TV dinners, they could talk about the show – and during commercials, they might share the details of their day.

But now, it’s all too easy to have an entire family staring at their phones while eating – watching and reading and focusing on their own individual interests, instead of talking to each other.

TV dinners may have helped women to get into the workforce. It’s probably a stretch to give too much credit to the TV dinner for that. Still, TV dinners did make it easier for dinner to get made, which became very important as more women – like Betty Cronin, certainly ahead of her time as a 1950s bacteriologist – entered the workforce. Somebody had to make dinner, and even a cooking-challenged husband or father could pop in a few TV dinners in the oven – and 25 minutes later, have a nice, piping hot meal.

And, indeed, Swanson executive M. Crawford Pollock, by now a vice president at the company, was referenced in some newspapers in 1955, paraphrasing a quote of his that married women in salaried jobs in particular would drive sales of frozen foods.

TV dinners helped build a multi-billion dollar industry. A marketing report on the state of the frozen food industry in 1954 and 1955 stated that there were 170 items being produced commercially, but that mostly stores were selling French fries, poultry and meat potpies, fish sticks and dessert pies. "Shortage of freezer cabinet capacity in retail stores is a difficult marketing problem,” the report noted.

Space is always a problem for new products to make their way into a supermarket, but the frozen food aisles are definitely now a prominent part of the grocery experience – and it’s still growing, partly due to Covid-19. In 2020, particularly, with more families staying home and not venturing out much, family meals were actually coming back in style, and the frozen food industry grew by 21 percent.

Frozen foods are a $65.1 billion industry, with the most popular items being frozen dinners and entrees, meat, poultry and seafood.

And, of course, popular culture changed. Society as a whole loved these TV dinners. So did, apparently, some celebrities. In 1962, Barbra Streisand told The New Yorker, “The best fried chicken I know comes with a TV dinner.”

TV dinners inspired many, many competitors. Banquet came out with a beef TV dinner in 1954, a year in which Swanson sold 10 million turkey TV dinners. Quaker Oats soon had frozen pancakes. In 1956, Mrs. Paul’s came out with frozen onion rings, which was revolutionary at the time, due to the breading issues, over these thing little onions. Well, you get the idea. The entire supermarket landscape was soon transformed.

But while TV dinners were advertised on TV, TV characters, best as I can tell, didn’t exactly embrace them right away.

Which makes sense. Swanson sponsored the first season of The Donna Reed Show, but I don’t remember any episodes where Donna Stone popped in a TV dinner into the stove. (But please correct me in the comments if I’m wrong.)

And can you imagine Alice on The Brady Bunch ever serving up TV dinners for the family? Laura Petrie on The Dick Van Dyke Show was a stay-at-home mom; she didn’t make TV dinners. Edith Bunker on All in the Family slaved over a stove; she, too, wasn’t about to give Archie, Gloria or Mike a TV dinner.

Generally, if you were a fictional woman in the 1950s and 1960s making a meal, it couldn't be a TV dinner. It would show that you didn’t care enough to make something homemade.

By the 1970s, TV characters were referencing TV dinners but the love affair between consumers and their TV dinners was clearly over. In the first season of The Odd Couple, when Felix discusses what he is going to enter in a cooking contest, he tells Oscar that he is going to hit the judges "with a simple American classic."

"You're going to make a TV dinner?" Oscar asks.

"Will you be serious?" Felix asks.

A couple years later, on Maude, Walter changes the subject during an argument with his wife and asks what she is making them for dinner.

Maude, incredulous, tells him that she’ll offer him a choice for dinner – chicken or roast beef.

Walter chooses the chicken, and Maude suggests that while she prepares dinner, he finishes making his martini and relaxes. Walter is pleased.

Moments later, she’s handing him a frozen package.

“Maude,” Walter exclaims. “That’s a TV dinner, and the chicken is still frozen.”

Maude cracks, “Walter, if you think that's a frozen chicken, wait till you see what you find in bed tonight."

In 1998, on The King of Queens, Carrie plans a simple Thanksgiving meal for herself, her husband, Kevin, and her father, Arthur.

Arthur isn’t too pleased when he sees what their Thanksgiving meal is going to be.

“TV dinners?” he asks, incredulous.

“All right, Dad, could you stop it? We’re going to have a lovely Thanksgiving dinner,” Carrie says. She shows him that the label on the package says, “A lovely Thanksgiving dinner.”

“You think they could put it on there if it wasn’t true?” she asks.

“I’m sorry. I was just assuming you were going to cook,” Arthur says. “You know, since your mother used to make such a big, beautiful meal every year.”

“I know, Dad, but Mom was a great cook. I defrost. That’s what I do.”

Arthur isn’t pleased. He talks about how his wife and Carrie’s mom would get up at dawn and “start peeling and dicing and shucking, every burner going. You’d walk into that house. You know what it would smell like? It would smell like love.” Then he adds, referring to the TV dinners: “But these are fine.”

Carrie, of course, decides to make a traditional Thanksgiving meal and chaos ensues.

The TV dinner also got little respect on The Simpsons. In a 1998 episode called “The Last Temptation of Krust,” Krusty the Clown bombs in a standup comedy routine in which he tells jokes about TV dinners.

“So, how about those TV dinners, huh? I tried one the other day. When lightning strikes, the peach cobbler goes out.”

Bart Simpson laughs. Nobody else does. (If you’re scratching your head, as I initially did, Krusty is suggesting that when lightning strikes, and you’re watching TV, your TV might go out. So if it strikes when you’re eating your TV dinner, the peach cobbler might go out. It’s a bad joke but supremely clever one, being The Simpsons. Still, you can see why the audience is so silent.)

Krusty continues his routine: “The other thing about TV dinners. You don’t have leftovers. You have – reruns.”

Total silence from the crowd. Not even a chuckle from Bart. Backstage, an animated Jane Garofalo, the comedian, who moments earlier was a big hit with the audience, whispers, “TV dinner jokes? Ooh, take that, Swanson’s.” Several comedians around her offer a little guffaw.

The really funny thing, though, is that Swanson dropped the phrase, “TV dinner” from their packaging back in 1962. They were worried that consumers might not realize you were allowed to eat their meals at lunch, too.

Clearly, Swanson executives didn’t have much faith in the intelligence of the consumer.

Whether they were right to drop "TV dinner" or not from their packaging, it was too late to remove the label from the public's consciousness. "TV dinner," as a term, had caught on. Forever more, every brand that has offered a frozen meal you could put in the oven, or a microwave, would be considered a TV dinner.

Only about 15 years after its creation, the TV dinner was arguably already considered iconic – and an everyday part of everybody’s lives. Oscar Madison was right to joke about the TV dinner being an American classic. In 1970, when The Odd Couple began, at the English High School, the oldest public high school in the nation, a time capsule was buried, and according to news accounts of the time, one of the items included was a TV dinner. As far as I know, at least as of 2013, the capsule hasn’t been dug up yet.

Meanwhile, Lou Grant may have summed up the average American’s feeling about the TV dinner in a 1971 episode of The Mary Tyler Moore Show called “The Square-Shaped Room.”

His wife is out of town, and Mr. Grant isn’t used to cooking for himself. He comes wearily into the newsroom. Mary Richards greets him with a hearty, “Good morning.”

“No,” Lou responds in a huff. “Any day that starts off with a leftover TV dinner for breakfast isn't a good morning."

Where you can watch some of the shows mentioned (at the time of this writing): The Mary Tyler Moore Show, the entire series, is on Hulu.com. The entire series of The Simpsons is on DisneyPlus. Maude can be found on Antenna TV. The King of Queens is on PeacockTV.com.

The previous "TV History 101": “Smile, You’re on Candid Camera!” The next "TV History 101" is about the early history of Saturday morning cartoons.

Mitzi Stricklin

Thanks for sharing very interesting we love this.